NCHS Data Brief â– No. 269 â– January 2017

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

Michael Albert, M.D., M.P.H., Pinyao Rui, M.P.H., and Jill J. Ashman, Ph.D.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed neurobehavioral disorders of childhood (1–3). ADHD is characterized clinically by inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development (4). This report describes the rate and characteristics of physician office visits by children aged 4–17 years with a primary diagnosis of ADHD. Four years of age was chosen as the lower limit because the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD begin at this age (5).

Keywords: ADHD • National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

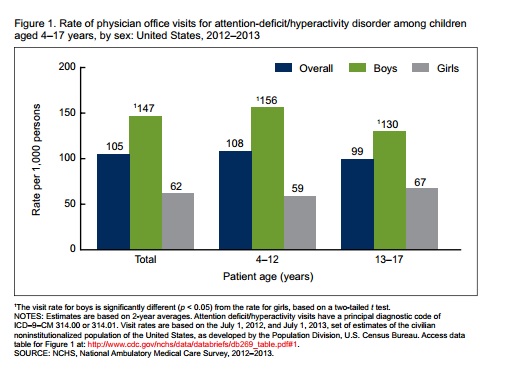

Did the ADHD visit rate vary by sex and age?

◠The visit rate for ADHD was 105 per 1,000 children aged 4–17 years, and was similar for children aged 4–12 years and 13–17 years: 108 per 1,000 children and 99 per 1,000 children, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Access data table for Figure 1 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#1.

◠The visit rate for ADHD was higher for boys than for girls among children aged 4–17 years (147 per 1,000 boys compared with 62 per 1,000 girls).The difference was observed within both age groups evaluated: for children aged 4–12 years (156 per 1,000 boys compared with 59 per 1,000 girls) and for children aged 13–17 years (130 per 1,000 boys compared with 67 per 1,000 girls).

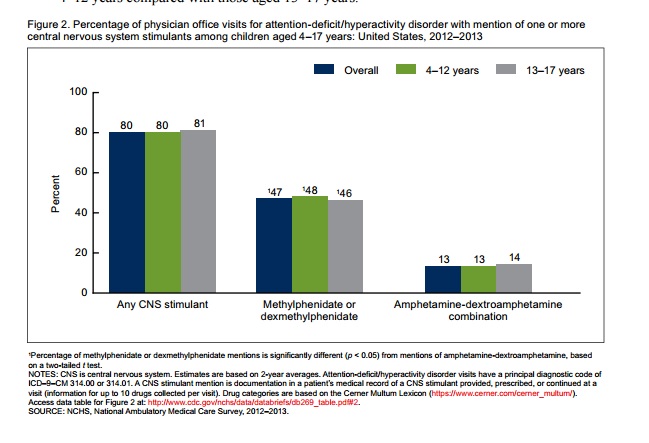

How frequently were central nervous system (CNS) stimulant medications provided, prescribed, or continued at ADHD visits, and did this vary by age?

◠CNS stimulant medications were mentioned (i.e., provided, prescribed, or continued) at 80% of ADHD visits by children aged 4–12 years and 81% of ADHD visits by children aged 13–17 years (Figure 2).

◠Methylphenidate or dexmethylphenidate was mentioned more frequently than the drug combination of amphetamine-dextroamphetamine at ADHD visits both for children aged 4–12 years (48% compared with 13%) and for those aged 13–17 years (46% compared with 14%).

◠No significant difference was observed in the mention of CNS stimulants for those aged 4–12 years compared with those aged 13–17 years.

Figure 2

Access data table for Figure 2 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#2.

Access data table for Figure 2 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#2.

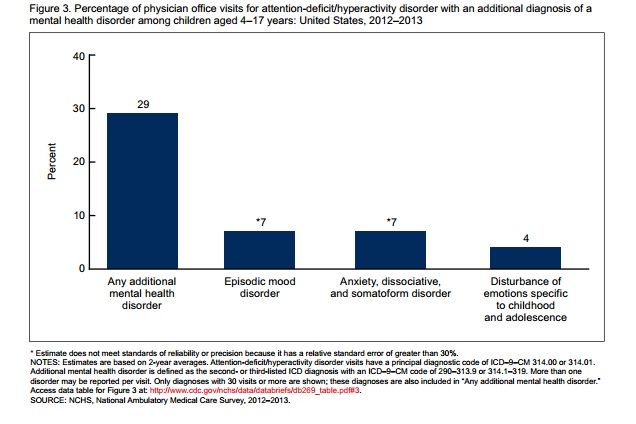

What percentage of ADHD visits had an additional mental health disorder as a second- or third-listed ICD diagnosis?

◠A total of 29% of ADHD visits by children and adolescents aged 4–17 had an additional mental health disorder as a second- or third-listed ICD diagnosis (Figure 3).

â— Additional mental health disorders included episodic mood disorder (7%); anxiety, dissociative, and somatoform disorder (7%); and disturbance of emotions specific to childhood and adolescence (4%).

Figure 3

Access data table for Figure 3 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#3. SOURCE: NCHS, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2012–2013

Access data table for Figure 3 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#3. SOURCE: NCHS, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2012–2013

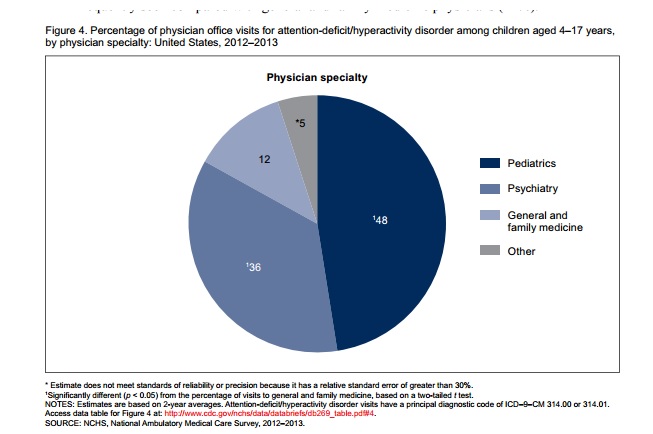

What was the specialty of the physician providing care at ADHD visits?

◠At 48% of ADHD visits by children aged 4–17 years, a pediatrician provided care and at 36% of visits a psychiatrist provided care (Figure 4).

◠At ADHD visits by children aged 4–17 years, pediatricians and psychiatrists were more frequently seen compared with general and family medicine physicians (12%).

Figure 4

Access data table for Figure 4 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#4. SOURCE: NCHS, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2012–2013.

Access data table for Figure 4 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269_table.pdf#4. SOURCE: NCHS, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2012–2013.

………

Summary

Health care utilization related to ADHD is of interest because the prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis among U.S. children and adolescents has increased in recent years (3,6,7). In addition, stimulant medications are commonly used to treat patients with ADHD, and public health monitoring of this practice has been recommended (3,7). This analysis indicated that during 2012–2013, an annual average of 6.1 million physician office visits in the United States were made by children and adolescents aged 4–17 years with a primary diagnosis of ADHD. This corresponded to a visit rate of 105 per 1,000 children. ADHD visit rates were higher for boys than girls among children aged 4–17 years and in the two age groups of 4–12 years and 13–17 years. Treatment with CNS stimulant medications such as methylphenidate or amphetaminedextroamphetamine was common for ADHD visits, with these medicines provided, prescribed, or continued in about 80% of visits among both children aged 4–12 years and those aged 13–17 years. More than one-quarter of ADHD visits among children aged 4–17 years had an additional mental health disorder listed as a second- or third-listed ICD diagnosis. Pediatricians (48%) and psychiatrists (36%) provided most of the care at ADHD visits by children aged 4–17 years, with 12% of the care being provided by general and family medicine physicians.

Definitions

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) visit: A visit with ADHD as the principal or first-listed diagnosis using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD–9–CM) codes of 314.00 or 314.01 (8). Additional mental health disorder: This includes all visits with a second- or third-listed ICD–9–CM diagnosis code from 290–319 (excluding 314.00 or 314.01 [ADHD]). Selected disorders and corresponding ICD–9–CM codes shown in Figure 3 include the following: episodic mood disorder (296); anxiety, dissociative, and somatoform disorder (300); and disturbance of emotions specific to childhood and adolescence (313) (8). CNS stimulant mention: Documentation in a patient’s medical record of a CNS stimulant provided, prescribed, or continued. Information for up to 10 drugs is collected for each visit. Drug categories are based on the Cerner Multum Lexicon (https://www.cerner.com/cerner_multum/).

Data source and methods

Data for this analysis are from the 2012–2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NAMCS is a national probability sample survey of nonfederal office-based physicians. NAMCS uses multistage probability sampling designs. Detailed information on the methodology of NAMCS, including changes to the survey that began in 2012, is available elsewhere (9,10).

In NAMCS for 2012–2013, a sample was made of 946 visits by children aged 4–17 years with a primary diagnosis of ADHD. Data were imputed for patient age (1.0%) and sex (2.3%). NCHS considers an estimate to be reliable if it is based on at least 30 visits and has a relative standard error of 30% or less (9). Estimates with an asterisk in Figures 3 and 4 have a relative standard error exceeding 30%. Mental health disorders with fewer than 30 visits are not shown in Figure 3. Data analyses were performed using the statistical packages SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) and SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.). Differences among subgroups were evaluated using a two-tailed t test (p < 0.05).

About the authors

Michael Albert and Jill J. Ashman are with the National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Care Statistics, Ambulatory and Hospital Care Statistics Branch. Pinyao Rui is with Karna, LLC.

References

1. CDC. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Facts about ADHD. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html.

2. Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS–A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(10):980–9. 2010.

3. Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour RM, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53(1):34–46. 2014.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC. 2013.

5. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management; Wolraich M; Brown L; Brown RT; DuPaul G; Earls M; et al. ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 128(5):1007–22. 2011.

6. Akinbami LJ, Liu X, Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children aged 5–17 years in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS data brief, no 70. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2011.

7. Visser SN, Zablotsky B, Holbrook JR, et al. Diagnostic experiences of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. National health statistics reports; no 81. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification. 6th ed. DHHS Pub No. (PHS) 11–1260. 2011. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm.

9. National Center for Health Statistics. 2012 NAMCS micro-data file documentation. Hyattsville, MD. 2015.

10. National Center for Health Statistics. 2013 NAMCS micro-data file documentation. Hyattsville, MD. 2016.

Public Domain

Original publication can be found here: Â https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db269.pdf

© 2006 – 2017 by The ADD Resource Center. All Rights Reserved.

To view HUNDREDS of articles and videos on ADD/ADHD, go to addrc.org

support@addrc.org 646/205.8080